by Miriam Kurtzig Freedman, J.D

Illustrations by Daphne San Jose

Let's go for it! It's a deal! It's what lawyers call, 'A meeting of the minds.'

Contracts happen all the time. They are everywhere! How many did you participate in today? Did you shop in a store? ride the bus? buy a car? eat at a restaurant? work at your job? attend a movie? Why are these common everyday events Kís? In each, one party makes an ìofferî requiring ìconsiderationî that the other ìaccepts.î For example, the store displays goods for sale (an offer) that the buyer wants and pays (acceptance) for (consideration): Voila! Thereís a K.

What is a K?

It's an agreement between two or more parties that requires each to do or give something in exchange. Once made, it is enforceable in court. In an important way itís an example of people making their own laws within the guidelines established by statute, courts, and tradition. In most cases, Kís involve the exchange of goods or services for money.

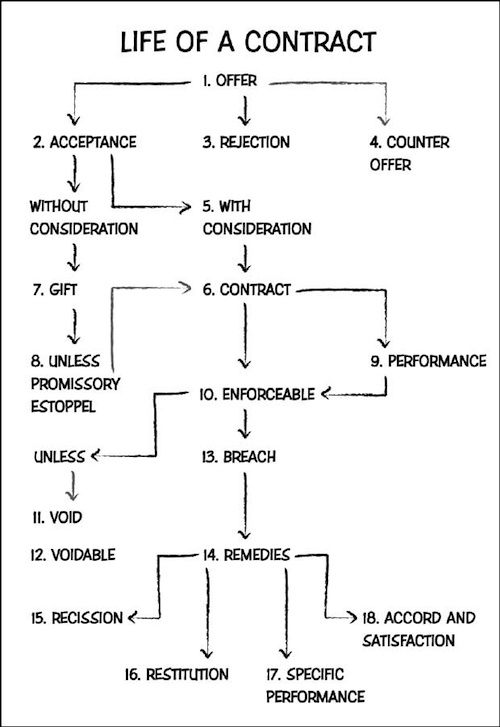

Below is a flow chart of the life of a K, followed by definitions of the legal terms in chronological order. (The numbers refer back to the flow.)

An action or indication by one party (the offeror) that he is willing to make an agreement with another party (the offeree). If accepted, it will create a K. A demonstration (manifestation) of the intent to make a deal.

The manifestation can be in many forms: spoken or written or displayed by action. When you walk into a restaurant and sit down, the owner offers to feed you and you indicate your acceptance by sitting down, ordering your meal, and eating it. Not a word about Kís is spoken! But youíve entered into one. Youíve clearly demonstrated - manifested - your intention.

Another example of an offer: 'I (offeror) will sell you (offeree) my car for three thousand dollars'.

Example of a non-offer: 'I am thinking of selling my car for three thousand dollars.' Even if you say youíll pay me the three thousand thereís no K because I never offered to sell it!

An offer needs four specific and definite terms: the who, the what, the price, the time.

An offeree agrees to the terms of the offer. 'Yes, I'll buy that car for three thousand dollars next week.' Your sitting down at the restaurant is an acceptance. Remember: silence can be a form of acceptance.

An offeree does not accept the terms of the offer, either by an outright rejection or by a counteroffer.

A change in the offer made by the offeree. For example, ìIíll buy your car for twenty-five hundred dollars,î or ìIíll buy your car if you wash it.î This is not an acceptance; itís a counteroffer. It does not create a K. Rather; it creates a new offer, this time by the (former) offeree.

Something of value exchanged for a promise or performance. ìIíll pay you twenty dollars for mowing my lawn.î Usually, consideration is required to make the promise binding and the K enforceable in court. Itís the quid pro quo (ìsomething for somethingî) of the deal. In this case twenty dollars and the mowing are the - mutual considerations.

The simplest definition is that it is an agreement between two or more parties. Each makes a promise that, if breached, is enforceable in court.

Contrary to popular belief, K's may be written or oral. So long as there is an offer, an acceptance, consideration, and other terms are satisfied (e.g., the parties have the required mental capacity, the subject of the K is not illegal, and so on), there can be an enforceable K, whether written or not.

But some specific K's must be in writing to be enforceable. These include:

In general and for these K's in particular; an important reason to ìget it in writingî is that writing memorializes the transaction. Memory can fail. If an argument arises later about any aspect of the K, the parties can prove their positions more easily if they are written down. ìBut you saidÖ,î ìNo, I didnít,î or ìGee, I donít remember,î arenít very persuasive.

A promise of performance given without anything of value in exchange. Usually, gifts or the promise of gifts are unenforceable.

Exception: A gift may be deemed a K under certain situations, in a quasi- K. The law may imply a K in order to promote fairness and justice. Unlike an explicit (actual) K it is not based on the partiesí mutual intent. Rather, itís based on the principle that a party has to pay for what he receives. For example, if a stranger finds your dog and feeds him for several days before you find the stranger and your dog, a K for the room and board for the dog may be created. Besides being grateful for the return of your ìbest friend,î you may have to pay for his care.

Did anyone say this would be easy? It may not be easy, but there is a certain beauty and fairness in it, isnít there? We move on!

An equitable (equity) doctrine that makes a promise binding, even if there was no consideration, if that is the only way to promote justice

.For example: Uncle Bob promises nephew Jim one thousand dollars after he graduates. Jim spends the money on a new TV before he actually gets the money. Later, Uncle Bob doesnít pay. If Jimís reliance on the promise was reasonable (Uncle Bob had kept his promises in the past!), then Uncle Bob may be estopped (prevented) from denying the existence of a K, even though, in fact, one had not been made. (Uncle Bob had, in fact, simply promised a gift.) The promise may be enforced, up to the amount already spent the amount relied upon. These cases rely on the facts: Was the reliance reasonable? Did Jim graduate? Et cetera.

A K that the law will enforce. You may take a K to court to seek a remedy if you believe the K was breached. Obviously, whether you win or not depends on the facts you present.

A K that may be canceled by one side. For example, a K with a minor may be voidable, if the minor chooses to cancel it. The minor may choose to do this at any time while he is still a minor. If he doesnít cancel it, then it may be enforced.

A K that is grossly unfair to one side (generally a consumer) may be voided by a court (not the parties themselves.) This is an equity principle, codified under the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC). It may be voided because it would be unfair, unconscionable, to enforce it. This is an example of the doctrine of unconscionability.Other voidable K's are those made by an unintentional mistake or through intentional fraud or misrepresentation or duress. Again, the dispute becomes a factual one.

A failure to carry out the terms of the contract. In legalese, it's 'wrongful nonperformance.'

When a breach occurs, remedies are used to right the wrong, to compensate the party whose K was breached. Remedies in law and equity include:

Forcing one party to perform according to the K. This remedy may exist in real estate cases, where a seller may be forced to sell the property to the buyer. The theory is that this is the only way to make the buyer whole, as no two properties are the same. Usually, you canít force a person to perform a job or service. Thatís slavery! It was outlawed after the Civil War by the Thirteenth Amendment!

Isn't it interesting how these various laws merge and interplay? Yes, what we learned in civics actually works!

The parties may agree to settle for less than bargained for in the K. This is a type of forgiveness. In effect a new K is -entered into. For example, the buyer might accept the goods later than promised without demanding a penalty.

Home - The Little Law Book - Legal Grind®

EliteAttorneys.com

2640 Lincoln Blvd, Box 6

Santa Monica, CA 90405

310.452.8160

info@eliteattorneys.com